Billie wrote this personal history around 2006 in response to requests from her children, some of whom wanted details about her life that were not revealed in the feminist-oriented essay she had produced a few years earlier. Her introduction to this narrative was simple:

Dear Reader, This is not a heavy duty memoir. It is simply a series of memories of my life before I became a mother. I hope that you get a picture of my life before you knew me. I give you this with my love.

EARLY CHILDHOOD

Family history tells me that I was born in a small house perched on a hillside  in Miami, AZ. A little mining town. My father was a clerk for the rail line that transported the ore from the mine.

in Miami, AZ. A little mining town. My father was a clerk for the rail line that transported the ore from the mine.

We moved to another small town, Bowie, which is near the historic Fort Bowie of western movie fame. My earliest memories are of my life there—and, of course, they are the most incomplete.

A large water tank sat near the tracks, visible from our house. Some unfeeling person must have told me that the Boogie Man lived there. My earliest fear.

The neighbor boy, probably 10 or 12, who died on a Boy Scout trek. I was too young to know the meaning of death—but old enough to understand its importance since I have remembered it all these years.

Walking with my mother to the drug store and meeting a gentleman who had always given me a nickel when we met. When the customary coin wasn’t offered I helpfully reminded him. My mother’s reaction was an early indication of the complexity of social exchanges.

More important events did not register in my memory bank. My brother, John Richard, was born while we lived in Bowie. I remember nothing about  this.

this.

My father was injured and spent a long time in a railroad hospital hi San Francisco and my mother began work as a waitress in the train station’s restaurant. Dining cars were not available on all passenger trains and regular stops were made to provide meals for the passengers. I have been told that I spent time with my grandparents in Kansas and my aunt in Oklahoma.

My only recollection of this change in the pattern of our lives was the change in the caregiver role which my father assumed during his recovery.

I think I was three or four when we moved to Tucson and lived in a group of houses owned by the Southern Pacific Railroad. These blocks of houses were provided for the employees, the presence or absence of luxury matching to the position of the employee. Ours was a triplex and I remember an evening with my uncle and cousin visiting us. This was during the decades when poliomyelitis was the menace which haunted parents. My cousin, Jack, became very ill that night. A high fever was a major symptom of “infantile paralysis”, as polio was called then. Jack’s fever was a true cause for alarm. No antibiotics had been developed so home remedies were the only resort. Mother’s was orange juice with Castor oil. It must have had some remedial effects; neither my brother nor I became ill. Jack endured a long recovery and was left with a limp.

A less dramatic memory of that time was a dash I made to the nearby elementary school. I was late—and afraid of my teacher’s reaction. I decided on my course of action; I would crawl into the classroom, avoiding detection. As I crawled on my way, I saw a pair of sturdy black adult shoes blocking my way. I stopped and looked up—way up—to see the teacher’s frowning face. My memory goes blank here.

This experience occurred at the start of my first school year. I finished that grade in Arkansas City, Kansas where my mother had gone to help her mother care for my grandfather who had undergone the amputation of his left arm, the operation followed by a tubercular infection.

None of this drama left an impression but I remember the basements in the houses, not a fixture in Tucson homes. Those basements were redolent with the smell of apples.

John (“Dick”), Billie, Essie, Hi, Joanne, Jay

Mother drove my grandparents and my young uncle back to Tucson. The Kansas doctors had determined that the desert climate would be beneficial for his recovery from the tuberculosis. A determination made by doctors all over the country at the time; Tucson became the mecca for tubercular patients.

None of us contracted tuberculosis, a miraculous result. Tuberculosis drugs would not be developed for many decades.

MIDDLE CHILDHOOD

My middle childhood years are perhaps even more vague than those of the earlier years, perhaps because we moved so often. My father incurred bar debts out of proportion to his salary so we moved frequently to ever-cheaper dwellings. Neighborhood grocery stores allowed customers to pay on credit and I dreaded their requests for payment. I was acquiring the twin emotions of shame and dread.

Joanne

Joanne was born in a house that was several steps above the little rental cabin which preceded it. Our family seemed to be on an upward path but that path turned down again not long after the birth. My father was a binge drinker and this particular binge took him to parts unknown for months. Mom was left with little money and with a baby, unable to look for work. I learned the dreaded word WELFARE and disliked intensely the pinto beans and prunes which seemed to be standard staples. An even stronger feeling of resentment swept over me when the good ladies of the local church brought food to our house. I knew even then that the gift was well intentioned but it also seemed to be patronizing.

Dad returned and the SP, as the Southern Pacific Railroad was known then, rehired him but assigned him to Gila Bend. Perhaps they saw it as a chance for him to dry out or perhaps to protect him from association with drinking buddies. We arrived there in the morning and had breakfast in a restaurant. Since I remember that fact it must have been a rare occurrence.

Our quarters were two cabooses which had somehow been joined together lengthwise with a tall live tree growing through the center. The straw-filled caboose benches were our furniture, except for Joanne’s crib that hung from four ropes fastened to the ceiling. This arrangement enabled Dad to read while he rocked the crib with one foot.

Gila Bend was, and is, one of the hottest towns in Arizona, and the months we spent there were pre-air-conditioning of any kind. Yet my only memory of the heat was the arrangement at church in which a large tub of ice was placed between the preacher and the congregation, with a fan blowing over the tub, directed at the congregation. I remember little of the school but it must have been a little backward in its curriculum development since they allowed me to skip the fourth grade.

Two social events stand out. My father took John and me to have dinner at the home of an African American family. At that time, Tucson was still a segregated community. The event must have made a strong impression for that reason and because I realized later that Dad came from a farming town in Arkansas. I do not remember hearing any bigoted expressions from him. He seemed to be completely comfortable that day and seemed to expect my brother and me to respond in the same manner. The other event was a trip to a Mexican-American home to buy Christmas tamales. Again, he did not appear to view this visit as extraordinary but even at that age, I sensed the prejudices exhibited by the Anglos, children and adults, in Tucson.

We returned to Tucson later that year and the next couple of years are not clear. There was the usual succession of houses, with Mom trying to make each of them as nice as she could. I do remember a frightening occasion in which I was the culprit. My parents were doing the laundry and sent me into the house to get some articles that were on the floor of their closet. I was annoyed because I was involved in the story line of the book I was reading. Trying to take as little time as possible away from my reading, I lit a match to look for all the pieces of clothing. The match flamed as it touched one of Mom’s dresses. I ran outside, repeating over and over, “I’ve done something awful but I can’t tell you what it is!” Fortunately, I became more specific and the fire department was called in time to limit the damage.

We moved again, perhaps because of the damage I had done. While we were renting this much smaller house, my brother, Jay was born. Not in our home this time, he was born in a hospital. I believe my aunt and uncle had moved to Phoenix so her overwhelming assistance wasn’t offered.

Less than a year later, we moved again to a somewhat larger home. While Dad continued working for the SP, Mom prepared lunch for 10 to 15 office staff members of the Civilian Conservation Corps. The CCC was one of the Great Depression projects undertaken by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. Joanne became very ill with an undiagnosed problem. It was severe enough to require a transfusion. Her blood type was rare and it was fortunate that one of the CCC employees donated blood for the little girl.

One of those men decided on a political run for the Arizona Corporation Commission. He hired John and me to distribute flyers in the surrounding neighborhoods. We approached this assignment with great enthusiasm but that enthusiasm dwindled sooner than the pile of flyers. We were soon depositing two or three at a time at each location. I felt some guilt then but it has been eased over the years because that was the only campaign tactic that he seemed to use. He probably would have lost anyway.

One of those men decided on a political run for the Arizona Corporation Commission. He hired John and me to distribute flyers in the surrounding neighborhoods. We approached this assignment with great enthusiasm but that enthusiasm dwindled sooner than the pile of flyers. We were soon depositing two or three at a time at each location. I felt some guilt then but it has been eased over the years because that was the only campaign tactic that he seemed to use. He probably would have lost anyway.

Mom’s efforts failed to achieve financial stability for our family. Dad left town, his destination unknown. She had to find a job to support her four children. Job opportunities were not plentiful during this time of the Great Depression so she was grateful when my uncle arranged a waitress job in a small restaurant. It was a 12 hour a day, 7 days a week position. There was only one-day care facility in Tucson and its fees were out of reach. Extended family members were the usual resources for “single mothers” (an unknown term at the time) but our family members were either unable or unwilling to provide a temporary home for my little brother and sister. A couple with whom Mom and Dad had been friendly in Bowie cheerfully answered Mom’s desperate plea for help and Mama Neta came to take the two little ones back to Texas with her.

Mom, John and I moved to a room in a stranger’s home in a section of Tucson known as Menlo Park. I don’t know if this name was influenced by the admiration of one of Edison’s fans.

Of course we had no car so Mom walked several miles to a her waitress job while John and I became “latchkey kids” (again, a term which would become popular decades later).

Within months Mom was offered a job at the newsstand and soda fountain of the railroad station. We moved to a little rental in Menlo Park. Mom had a split shift that meant that she was absent in the evening. I became guardian, housekeeper and chef for both of us. My memories don’t provide details of adult performance of those duties. We saw a lot of movies and I catered to his preference for fried bologna sandwiches.

John and I were able to make several one-day trips. Since Mom was now a railroad employee we traveled for free and four or five times John and I left early in the morning for El Paso, Texas or Los Angeles, returning in the evening. We spent the hours exploring the neighborhoods around the depots.

Jay

Dad returned a year later and Mom took him back—again. The SP rehired him and Mama Neta brought the little ones back to Tucson. My memory of their return is all too vivid. Joanne remembered Mom and went willingly to her arms. Jay, a year younger, screamed at leaving Mama Neta’s arms. The anguish in my mother’s face was painful to see.

We moved to a triplex near the railroad station, close to both Dad and Mom’s jobs. Mom continued to work until her retirement as a railway clerk. We were living there when I finished my freshman year—part of the junior high school curriculum.

Strangely, I can remember John playing Finlandia as part of his trumpet lesson assignment. He delivered the morning paper and a weekly magazine, earning enough money to buy a black English racing bicycle with hand brakes. I was envious, both of the bike and the amount of money he had accumulated. Baby-sitting was the only job open to young girls. It was not easy to amass a fortune with a starting point of 25 cents an hour.

The intact family moved again as our family fortune improved, this time to the only house we ever owned. It had two bedrooms and a sleeping porch so that Joanne and I shared a room; the boys shared the sleeping porch. The house was a few blocks away from the high school that I was soon to attend. During the preceding months I spent hours looking at magazines devoted to prep fashions and dreaming of the twin sweater set that would gain me entree into the popular crowd.

More important concerns arose. Jay contracted diphtheria and was seriously ill. I recall listening in my room to the muted voices of two doctors as they discussed his condition. In those days the homes of persons with infectious diseases were quarantined, that is no one was allowed in the home and only one family member could leave the house to work and bring in necessary provisions. This was my father’s role.

I had a minor role in this drama. All of us were given diphtheria antitoxin injections. After my shot was administered, I was lying alone in my bedroom when I began having trouble breathing. I was experiencing an anaphylactic reaction in which all the body’s tissues begin to swell, including the ones in my throat. Fortunately, my sister, only four years old, came into the room, sensed my distress, and ran for help from the doctors in the next room. Another shot, this one of adrenalin, brought me back to a normal state.

After we recovered from the diphtheria scare, John and I returned to school. Within weeks the quarantine sign went up again—chickenpox this time.

YEARS IN TRAINING

September 1941 came and I started my life as a “probie.” This was the term for us in our first six months of training to become nurses. We were on probation and wore a uniform reflecting our lowly status. It was a starched blue dress, with a large white collar and, for no known reason, a long black silk scarf tied around our neck and reaching almost to the hem of our dress. It was kept in place by the matching blue belt.

At entrance, we were given psychological profile assessments. The director of nurses gave me the results of my tests. She sympathetically told me that I was much too shy and retiring. She cautioned me that I must overcome those qualities if I hoped to complete my three-year course.

Nursing School Photo

We began our daily routine of working on the different floors of the hospital. Fourth East had mostly private or semiprivate rooms; the other floors had more wards with at least four patients. Initially, we were assigned to caring for the patients’ needs on these floors where they were awaiting diagnoses, receiving medical treatment, or recovering from surgical procedures. We would not receive training in the specialty areas until after the first six months.

My memories of nurses’ training are vivid, some because they were so tedious, some because they were so traumatic. We learned how to make a hospital bed, inhering the corners of the top sheet and including a fold at the bottom so that the sheet would not press upon the patient’s feet. We learned to make these beds with the patients in them, following their bed baths. Our nursing supervisor during this training period was Miss MacDonald, a soft-spoken but demanding Scottish woman. Some of her instructions and admonitions were:

“When you are changing a bed, nothing should be on the floor but feet and furniture.”

“You should always maintain a professional distance from your patients because familiarity breeds contempt.”

I am quite sure that admonition was meant for our conduct with male patients—as is the following:

“The nurse will wash down as far as possible, up as far as possible, and the patient will wash possible.”

I remember my first patient, a sixty-year-old woman whom I cared for until her death from cancer. Death had always been a philosophical concept in the many books I had read. This was different. Life had left this woman’s body. What had made her a living creature was gone.

Not long after her death, I worked on the Pediatrics ward, caring for a two year old little boy whose picture is still in my photo album. Leukemia took his life.

We worked at least four hours a day during this probationary period, attending classes for an additional four hours. The classes were taught by doctors or nurses, many of them people with whom we would be working.

There was a small graduation ceremony at the hospital when our probationary period was over. To demonstrate our new status we were given the white cap worn by Good Samaritan graduates and this was the cap that we would wear for the rest of our professional lives.

We began a three-month rotation in all the specialty areas: obstetrics, pediatrics, surgery, emergency room or diet kitchen. These rotations still included providing patient care on the floors.

Our shifts were 7 to 3, 3 to 11, and 11 to 7. For those who were working the first shift, our day began before breakfast with attendance in the chapel. Good Samaritan Hospital was under the auspices of the Methodist church. We sang two hymns, selected by each of us in turn, and listened to a short sermon. I recall feeling very daring when the choice was mine and I always chose pages 178 and 210. Miss Ryan, our prim housemother, who conducted the chapel program, apparently never got the point of my attempted humor. The songs were titled: God Send Us Men and Yield Not To Temptation.

Nor was I totally aware of the implication because all my experience in such matters had been garnered from my reading.

Men were available. My training began in September 1941; Pearl Harbor happened on December 7, 1941. Within months, Phoenix was ringed by air bases training cadets as future pilots, navigators, or bombardiers. Downtown hotels began to offer dances to which the airmen and local single women were invited. I attended many of these dances, occasionally being caught by Miss Ryan when I came in after curfew. Even our off-duty hours were strictly supervised and each violation earned a demerit. I accumulated many demerits.

Immediately after the attack on Hawaii, Arizona hospitals received notice to be prepared to receive patients from California hospitals. Attacks on California were anticipated but didn’t occur. We did receive from some governmental source a large supply of sandbags but we were never told just what we were to do with them.

The war did have a very strong effect upon us, however. Doctors and registered nurses answered calls to duty during the next year and our hospital became seriously understaffed. We student nurses were the major labor force, with only one R.N. supervisor on each shift. Our hours became longer and longer; and an eight-hour shift was a thing of the past. If things got busy in surgery, obstetrics, or emergency room, it was not uncommon for us to work another twelve hours.

I remember being the surgical nurse for one obstetrician as he performed four surgeries in succession. Following the lengthy operations, I went down to the classroom to take a final test for the course he taught. I had not slept for 24 hours and soon put my head on the desk and slept, failing the test.

On another occasion, I assisted a surgeon who was performing an operation on the brain of a woman who had been in a car accident. The patient was the wife of the surgeon’s partner.

In my final year of training I was able to receive two additional rotations in surgery and in the emergency room. Both of these rotations were exciting, never boring.

One evening in the emergency room, a young man brought his wife to us. She did not respond to any of us. She sat quietly on a bench singing “Let Me Call You Sweetheart” over and over. Her husband said that this behavior had been repeated for six hours.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W9pr3kTutbs]

Our class was to graduate in September 1944 and the war was still being fought. The armed services were pleading for student nurses to enlist after graduation. The federal government offered a program in which enrollees would be called “cadets”, wear designer uniforms, and receive $35 a month. (Our monthly pay was $5) Upon graduation, the nurses were to join either the Army or the Navy Nurse Corps.

The American Red Cross coordinated the program. Some of the senior nurses received information from them and asked our Superintendent of Nurses if the Good Samaritan Hospital would participate in the program. She refused, stating that there would be too much paperwork involved.

I organized a meeting and our group of seniors notified the Superintendent that we would not be going to work that day. The hospital, of course, could not have functioned without us so she soon promised that the program would be adopted. We reported to duty; a strike had been averted.

Unfortunately for me, I had revealed my true age because registration was near for the next State Board examination. Because I had lied, I was denied admittance to the cadet nurse program.

Remember the admonition I had been given to overcome my shyness?

THE ARMY YEARS

Billie’s Class at Madigan General Hospital

I remember locating a ride in a car pool. I was picked up early—very early—in the morning at my home. I climbed in and went back to sleep until we arrived at the Base. The work was sedentary, hours and hours before the typewriter. I could be wrong but it seemed as though I typed the same page over and over.

I remember locating a ride in a car pool. I was picked up early—very early—in the morning at my home. I climbed in and went back to sleep until we arrived at the Base. The work was sedentary, hours and hours before the typewriter. I could be wrong but it seemed as though I typed the same page over and over.

One pleasant memory remains of that time. My little brother and sister came to the Christmas celebration, to which Santa Claus arrived in an airplane, carrying his bag of toys for all the young guests.

In the early months of 1945 I passed the State Board examinations. I could start my career as a registered nurse. An invitation came from a former supervisor to join her in the nursing staff at Tucson Medical Center, a new community hospital. Several memories stand out—giving intramuscular shots of gold to arthritic patients and giving many intravenous shots to relieve patients suffering from asthma. A popular remedy for alcoholics was the use of Vitamin B injections. There are trends in medicine.

The war in Europe was winding down but many of the islands in the Pacific were still in the hands of the enemy. The need for nurses was so great that one of the Houses of Congress initiated a bill that would draft nurses—but not as commissioned officers. The bill was pending in the other House. I went to the headquarters of the American Red Cross that was the recruiting center for nurses. My preference was the Navy Nurse Corps but my myopia prevented that. I was in the Army Nurse Corps in May 1945.

VE Day (Victory in Europe) was May 8; I left Tucson May 9. My mother who took me to the train station was probably the only person there with tears in her eyes. My train arrived at Madigan General Hospital at Fort Lewis, Washington. It was here that I would begin my career as a second lieutenant in the U. S. Army Nurse Corps.

Two sergeants were charged with the duty of molding twenty nurses into the Army pattern. Two major parts of their program were calisthenics and long lectures introducing us to Army procedures. They warned us repeatedly of the necessity of learning all this material, implying that dire consequences would result if we did not accomplish this. There were evenings following long, long days of class and calisthenics when we thought that the consequence might not be so bad if it meant that we could quit and go home. But that was not the intended consequence.

It rained almost every day in the six weeks of basic training. To add to the overall dismal atmosphere we were given a complete series of shots, including ones for potential overseas duty. The culmination of basic training was a forced march into the woods. We were then to dig a slit trench for the individual tents we were going to erect. I completed the march (forced to, as it were) but I finished neither the trench nor the tent before the evening mess. This meal was served in the form of K rations, a metal can of food. One of the sergeants announced that, predictably, one of us would cut our hand on the key that opened the can. I quickly learned that he was right as I looked at my bloody hand.

After a restless night spent in a sleeping bag on the ground in my lopsided tent, we ate another K ration before we went for another forced march. By this time I knew that a forced march was a very fast march. As we started off, we were told that an airplane would fly over, simulating an air attack. We were to hit the ground immediately. The plane swooped over us; I hit the ground. But, literally, it wasn’t ground that I hit. A cow had been in the meadow before me and had made a significant deposit.

We marched back to camp. We took down our tents, filled the trenches, and marched back to Ft. Lewis. Pictures were taken of our group, now clad hi dirty khaki fatigues, wearing combat boots, and a metal helmet that fell to our eyebrows.

Reaching into my memory bank for this section, I have been surprised at how few memories of my patients were recorded. I believe that part of this dearth is due to the fact that we ward nurses did not do the bedside nursing to which I had become accustomed. Medical corpsmen conducted these duties while we nurses were primarily pencil pushers.

I remember 11 to 7 shifts on a large neuropsychiatric ward. They were actually two wards joined by a central hall; the wards and rooms were locked with the huge rings of keys which I carried. I had one corpsman to help me with these desperately ill men; I would complete one round of medications and then begin it again. The trend in these closed wards was the use of large doses of insulin to produce a comatose state, with an expected outcome which was similar to the outcome of ECG, electroconvulsive therapy.

One night, about 3 AM, one of the patients (who had not been locked in) came into my office, looked steadily in my eyes and said, “You think I’m crazy, don’t you?” I only remember pondering the correct answer; I don’t remember what it was.

I had the responsibility of another double ward. These patients were the soldiers who had been liberated from the Japanese prisoner of war camps. They were emaciated and almost feeble. I was working there on August 15, 1945 which was VJ Day (Victory over Japan). The rest of the hospital celebrated wildly. My patients were quiet, not in a celebratory mood.

The news of Enola Gay’s delivery of the A bomb over Nagasaki and Hiroshima came to us while we were having dinner in the officer’s mess. Ironically, seated at my table was the Commanding Officer who had been the CO of the army hospital at Pearl Harbor on December 7. Those of us at the table had conflicting emotions—elation that the long war was over but disturbed by the implications of the use of an atomic bomb.

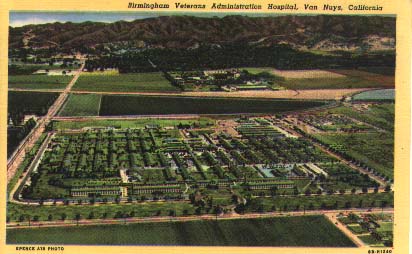

Our hospital was taken over by the Veterans’ Affairs Department and the patients were all to be paraplegics. We were transferred to other hospitals which were still under Army auspices.

Pasadena General Hospital (today)

I had not been a faithful follower of Army regulations. I was reprimanded twice in my Army career. The first time was for wearing a civilian dress under my Army coat (I was going to Desi Arnaz’s opening night at Giro’s on Sunset Strip. The second time was for dating an enlisted man; I broke the rule about fraternization.

UNIVERSITY YEARS

I was stationed at the Pasadena Hospital when I read a poster on the bulletin board. The poster announced that Congress had passed the G.I. Bill. After I received my separation papers from the Army, I would be able to return to Tucson and enroll at the University of Arizona. My tuition and books would be covered and I would receive $75 a month. My dream had come true. Because I had an established career, I did not begin with

the idea of developing a major. I remember that first year in which I took American Literature, History of Philosophy, History of Psychology, Botany, and Economics, relishing each moment. I was a senior before I decided that I had so many credits I should declare a major and receive a bachelor’s degree. I had almost an equal number of philosophy and psychology classes but psychology won the toss.

The photo is of Don Robert Underwood next to a trainer, probably in Montana flight school.

After my first years at the university, I married Don Robert whom I had met at a party in the Officers’ Club of the army hospital. The party’s theme was a shipwreck and everyone wore some kind of costume appropriate to a shipwreck. Don R wore his pajamas and bathrobe, as did many of the other patients. However, the silver bars on his shoulders and the pilot wings on his chest distinguished his outfit.

Billie and Don in Nogales

Just before my graduation in May 1950, the head of the department told me that I would receive the Phelps Dodge scholarship to begin studies for a master’s degree. I thanked him for the honor but declined. Mark was to be born in October.

Thus began motherhood.